It was a warm summer day in June 2022. *Layla Williams packed all her belongings into four big suitcases and boarded a flight from Stockholm to London with her three children. Upon arriving at her mum’s house in Haringey in North London later that day, she called her husband. “We are not coming home ever again.”

That day, Layla fled the man who had abused her physically and emotionally after eight years of marriage. Unhoused, fleeing domestic violence and struggling with PTSD, she turned to Haringey council for help. But instead of finding safety and stability in London, Layla and her children have spent the past two and a half years trapped in a single, cramped room in temporary accommodation in Tottenham, North London.

I recently spoke with Layla to find out more about her situation. Over the past year I have been organising with the London Renters Union and I have been involved in housing justice struggles more generally. In that time I’ve met many people like Layla, unhoused or temporarily housed, stuck in a limbo, waiting to be placed in a council flat.

“I thought Haringey council would look at my situation and help me, at least try to,” Layla shares. “They know about my PTSD, but they have offered me nothing, absolutely nothing.” Instead, she says, they have left her alone in accommodation that has only deepened her trauma.

Layla sits in a small office space on the ground floor of her accommodation. The room is just a few square metres in size, with two tables, three chairs, and bare white walls. Old faded blinds are dangling off the ceiling. It is the only place she can speak to me; the kitchen area is busy and her kids are in their only room.

Escaping violence, entering uncertainty

For years, Layla had been too scared to leave her husband. She and her family lived in a house in a forest outside Örebro, Sweden. She barely spoke Swedish, knew no one apart from his family, and believed she had no way out.

But then came the final straw. “My husband beat me in front of the children,” she tells me. “I was left in a lot of pain and covered in bruises. I couldn’t get off the bed and I couldn’t move my arm. He refused to let me go to the hospital.”

At that moment, Layla knew she had to leave. “I had to pretend everything was fine while I was planning the move,” she explains. “I told him we were going to visit my mother in London for the summer break. He didn’t know we weren’t planning on coming back.”

That should have been the end of Layla’s trauma. However, three years later, she is still unhoused and stuck in the same temporary accommodation, where the family of four live in a single room. The room is lined with suitcases and bags, the only way to store their belongings. They share two toilets and two kitchens with seven other families.

Unsafe and unsettling

Having to share the small space with other men – whether in the bathroom or kitchen – is triggering, Layla says. One time, she saw one of the men intimidating and threatening his wife. That situation, she recalls, was unbearable. She reported it to reception, but as a result, the man began intimidating her as well. “After that, I started isolating myself even more. If I don’t have to leave my room, I won’t,” Layla says. “If I need to use the bathroom, I’ll go, but that’s it.”

Living in temporary accommodation has hugely impacted her sense of safety. “I’ve developed an obsession with locking doors,” she confesses. “I’ll check the door five times before I feel comfortable enough to take my clothes off and get into the shower. I’d never done that before I came here.”

Even in her room she doesn’t feel safe. “Sometimes, the most I sleep is two hours. If I stay somewhere else overnight, like at a friend’s house or my mum’s, I might get a good sleep. But here, you can’t sleep.”

Women and homelessness

Unfortunately, Layla’s situation is not uncommon. Government figures show there are officially 117,450 households in temporary accommodation, including more than 150,000 children. This is the highest number on record. Originally, temporary accommodation was supposed to provide unhoused people with short-term and temporary housing while they were waiting for the council to provide them with permanent housing. But many like Layla, spend months, years and sometimes decades in unstable, unsuitable housing.

Women are disproportionately affected by homelessness. In London, they make up 65% of all people living in temporary accommodation. Single mothers like Layla are especially at risk, with 1 in 38 single mothers facing homelessness. In many cases, domestic abuse is the driver.

To find out more about the challenges women face when they are unhoused, I spoke to Hannah Bradburn. She works for Lawstop, a legal aid firm providing legal support for unhoused people, migrants and tenants struggling with their landlords.

“Women are not only more likely to be homeless because of abuse – women and queer people are also more likely to experience violence and abuse when they are homeless,” Hannah explains. “When unhoused, there is a high risk of re-traumatisation or even reabuse”.

No protection for domestic abuse survivors

Despite the added risks, councils often fail to protect domestic abuse survivors. For the past two years, Layla tried contacting Haringey council repeatedly, explaining that her living situation severely impacts her mental and physical health, as well as her safety. It couldn’t be clearer that she needs more suitable housing for herself and her family.

But she’s rarely dignified with even a response. “The only reply I receive is a generated email saying that Haringey is overwhelmed and that there is a shortage of housing. I just can’t believe that this is the best they can give us in three years.”

Hannah continues: “Councils should provide emergency and temporary accommodation that are for women only. It is clear that living with other men when you are traumatised from male violence is not suitable accommodation.”

I believe that it all boils down to Hannah’s parting words to me: “A lot needs to change, but I would say that the main issue underneath it all is that we do not have enough social housing.” As long as not every person has access to decent and safe housing, no policy change will ever truly protect domestic abuse survivors like Layla from living precariously. And after decades of austerity and neglect this seems further away than ever.

How the UK sold off its council homes

In London alone, more than 300,000 people are waiting for a council home. In the whole of the UK the number is at 1.6 million, with some people waiting for up to 10 years.

Subscribe to shado's weekly newsletter

Exclusive event news, job and creative opportunities, first access to tickets and – just in case you missed them – our picks of the week, from inside shado and out.

Ever since Thatcher introduced the Right to Buy in 1989, councils all over the country sold off their homes and their land to private landlords and developers. More recent governments have continued this trend by implementing policies that prioritise home ownership and market-led solutions over social housing. New Labour maintained the Right to Buy policy, which led to a loss of 484,000 homes in 13 years of New Labour’s government.

Moreover, 107,468 council homes were demolished in that period. New Labour also barred Councils from applying for ‘social housing’ grants to build new homes. Instead, only housing associations were allowed to apply. Housing associations are private companies and this led to even more loss of council housing.

Conservative-led governments accelerated this trend by expanding Right to Buy discounts, and introducing policies like Affordable Rent, which allowed housing associations to charge rents at up to 80% of market rates – far higher than traditional social rent. In 1979, there were 6.5m council homes; now there are 2.2m, while 4.4m households rent privately, twice as many as 15 years ago.

To make up for this, councils rent out accommodation from private landlords to house those who would otherwise be unhoused. In the last year alone local authorities all over England have spent over £2.29bn on temporary accommodation. This means that billions of public money is transferred to private landlords each year. Money that could be spent on social housing. Instead of further filling the pockets of landlords with taxpayer money, councils should invest the money in buying back private land and building public homes.

With rising rents and an ongoing cost of living crisis, things will only get worse. If national and local authorities do not stop this spiral, more and more people will be pushed into temporary accommodation and homelessness, risking the mental and physical wellbeing and quite literally the lives of the most vulnerable people in our society. Among them are single mothers, ethnic minorities, disabled people and children.

The emotional toll of temporary accommodation

Layla worries about the impact her living situation has on her children. “My children are very embarrassed,” she says. “They don’t like people knowing about our situation. They can’t really invite friends over. It’s not somewhere you would bring someone to visit. They can’t do normal children’s things.”

The toll on their mental health is undeniable. Her daughter, in particular, often comes home in tears. “Kids have mental health too,” Layla says softly. “They’re stressed and frustrated. They’re growing up in a place where they can’t feel settled. And as a mother, that’s heartbreaking.”

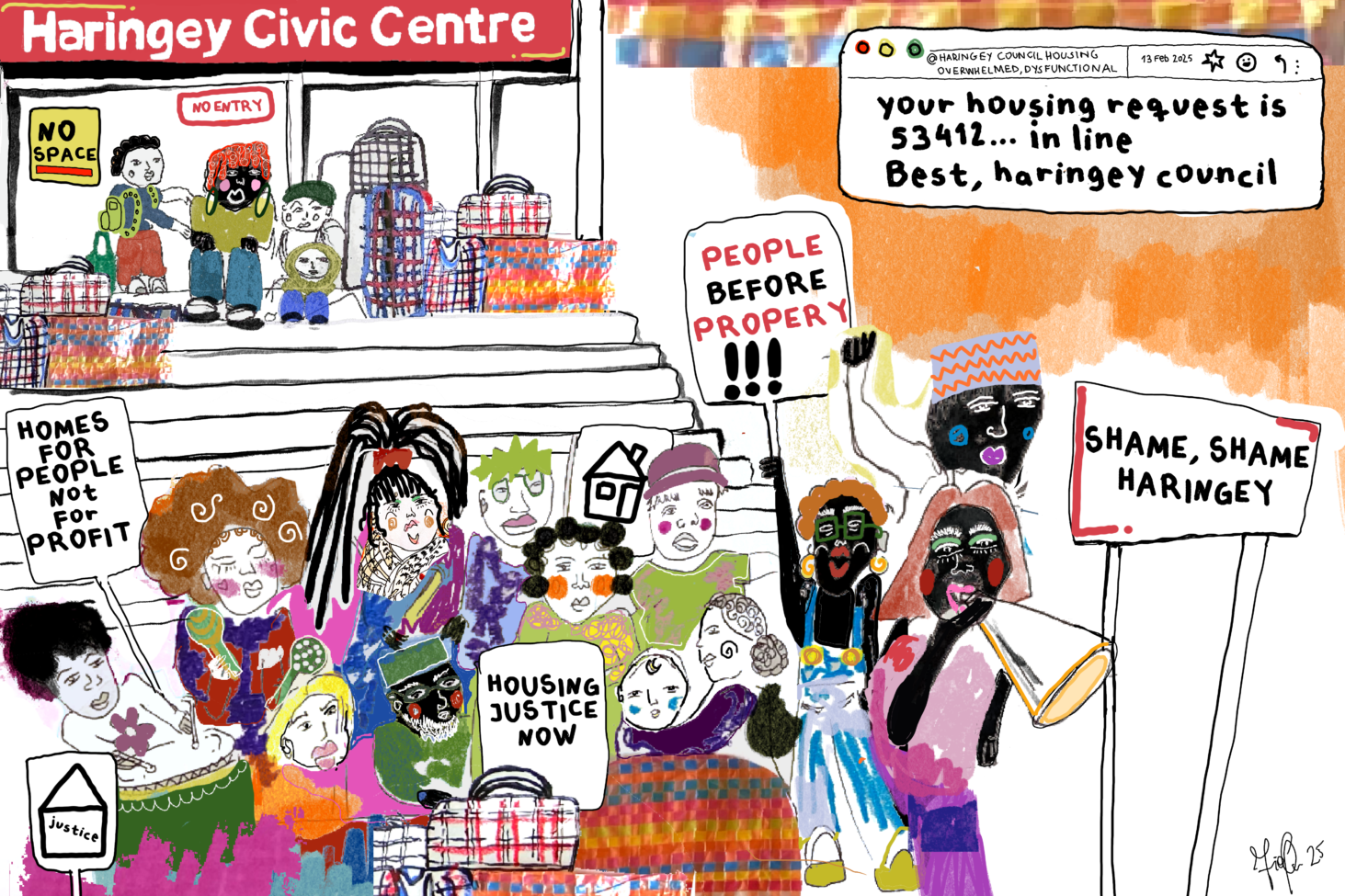

At the end of last year, Layla was tired of fighting the council all on her own. She reached out to Acorn Haringey, a community organisation advocating for tenants’ rights. They helped her stage two protests in front of the council, hoping to speak to someone responsible.

However, the council ignored their protests. On their last attempt, in February 2025, they were chased away by private security. “I think they forget that we’re real people living real lives,” Layla says. “You know, we’re more than just properties and houses, we are people with feelings who are going through things.”

Most days, Layla tries to stay hopeful, but she admits: “It is starting to feel like we’re going to be here forever.” All Layla and her children long for is stability and a bit of privacy. “Apparently, it’s too much to ask for somewhere I can cook; somewhere I can go to the bathroom without feeling uncomfortable.”

When I asked Haringey Council to comment on Layla’s situation, Councillor Sarah Williams, who is Haringey’s Council Deputy Leader and Cabinet Member for Housing & Planning, said:

“We fully understand that living in shared accommodation of this nature is far from ideal and appreciate the challenges Layla is facing. However, like all London boroughs, we are dealing with a homelessness crisis with huge demand for assistance while our options for securing self-contained accommodation are severely limited as landlords leave the market or request their properties back.”

Haringey Council’s response once again proves the incompetence of so many local authorities to protect their tenants in the face of the housing crisis. While families like Layla’s wait endlessly for a safe and stable home, councils have yet to put forward real, radical solutions. But tenants like Layla are increasingly refusing to accept their silence and neglect. By joining forces with other tenants, they are building power, demanding change and showing that resistance is possible – even in the most difficult circumstances.

*name changed for safety reasons

What can you do?

-

- Join a tenants union, in London there is the London Renters Union

- Join Acorn, a community union

- Join raid and eviction resistances

- Read about the Focus E15 Mothers, a group of single mothers that took over a block of empty council flats after being evicted from their hostel

- Check out activist Kwajo Leon Tweneboa campaigning for safe and decent housing

- Read: What just housing policies mean for climate justice

- Read: What is Gentrification?