Our Sexpert Tara talks through the complexity of feelings and stigma around abortion, and how to find hope and community

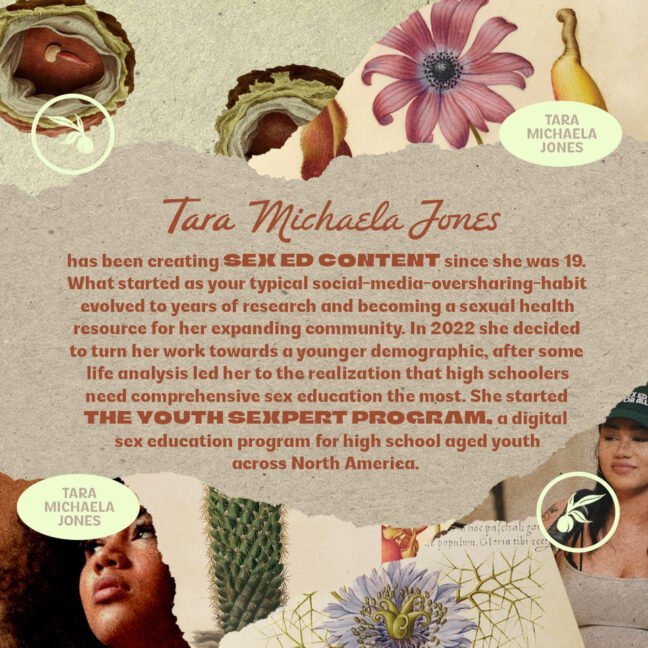

Tara Michaela & Image: Alex Francis

An orgasm is a series of involuntary muscle contractions, typically occurring in the vagina, penis, uterus, and/or anus. These contractions happen about once per second, usually 5-8 times, and are accompanied by a surge in blood flow to the brain. When a pleasurable feeling is building up, it might be hard to identify the endpoint or climax. A feeling of pleasure that is rising and then a feeling of release is a huge part of how you can identify that.

For people with penises, penile orgasm especially is often (not always) associated with ejaculation, which tends to happen 2-3 seconds after orgasm.

Other signs of an orgasm are as follows:

● Pupils dilate

● Heart rate increases

● Heightened genital sensitivity afterward (this has to do with what is called a refractory period: the time period after an orgasm where you are physically unable to orgasm again. People with vulvas as opposed to penises tend to have shorter or non-existent refractory periods).

Orgasms can feel different from person to person and even vary for the same individual depending on factors like mood, arousal levels, and stimulation methods. Some people have “good” and “bad” orgasm days, while others may notice distinct sensations depending on which part of the body is stimulated. Though the clitoris and penis are primary sources of orgasm, other erogenous zones, like the G-spot, anus, nipples, or even toes, can also trigger an orgasm for some.

Orgasm is one stage of what is called the sexual response cycle:

● Stage 1: Excitement

Associated with the term “foreplay”, this is when the body begins to respond to arousal. During the excitement stage muscles tighten, nipples harden, breasts can swell, increased blood flow to the genitals can cause the labia minora or testes to swell. You may notice vaginal lubrication or precum.

● Stage 2: Plateau

A continuation of the excitement phase, the body prepares for orgasm. The parasympathetic nervous system (which controls the body's fight-or-flight response) is activated, causing breathing, blood pressure, and heart rate to rise. In people with vulvas, swelling can lead to a visible color change (often purplish) in the genitals, and the clitoris becomes more sensitive.

● Stage 3: Orgasm

As described above, this is the peak of sexual response. Characterized by muscle contractions and a release of tension.

● Stage 4: Resolution

After orgasm, the body gradually returns to its resting state. Heart rate slows, muscle tension relaxes, and genitals return to their pre-arousal size and sensitivity.

Understanding your body’s responses can help you recognize and improve upon your experiences with pleasure. Though I must say, focusing on what feels good rather than meeting a specific expectation is the key to more satisfying sex overall.

Most experts (sexuality professionals, physicians, OBGYNs, urologists, etc.) will advise you to remember one of two rules.

Get tested for STIs between each new sexual partner

Get tested for STIs once every three months

The truth is that for each of us, one rule will feel like a better fit than the other. Getting out of a year-long monogamous relationship? You might not have gotten tested every three months during that time, but now that you’re considering putting yourself out there and potentially meeting new people, getting tested between partners makes the most sense for you. Do you regularly have one night stands but swear by your barrier methods (condoms, dental dams)? Well, holding yourself to “once every three months” is a great way to maintain some peace of mind and prioritize your health.

There are a few ways we should contextualize these two rules of thumb. The first is that the goal here is safeR sex; there is no such thing as safe sex. Virtually every act mainstream society considers sexual carries risks to our physical health. I say this not to scare you, and I hope it doesn’t. Every STI is either curable or treatable. These health conditions are stigmatized entirely because they are related to something as morally contentious as sex, not because they are a death sentence. In fact, they are very common. Around half of all people will have or have had an STI by the time they turn 24.

Curable:

● Chlamydia: A bacterial STI that can be treated with antibiotics

● Gonorrhea: A bacterial STI that can be treated with antibiotics

● Syphilis: A bacterial STI that can be treated with antibiotics

● Trichomoniasis: A parasitic STI that can be treated with antibiotics

Treatable, but not curable:

● Herpes: Antiviral medications can help manage the disease, but there is no cure

● HIV: Antiviral medications can help manage the disease, but there is no cure

● Hepatitis B: Antiviral medications can help fight the virus and slow liver damage, but there is no cure

● HPV: Most types of human papillomavirus (>90%) are low risk and your immune system clears it up on its own without causing health problems. The fewer types that cause cancer are harder for the body to get rid of on its own.

“SafeR sex” as opposed to “safe sex” reminds us that there is no one size fits all. We all have different levels of comfort with risk. For example, many people do not use barrier methods when performing oral on a penis, nor do they regularly get their throats swabbed during STI testing. This isn’t inherently a “no-no”. There are fewer STIs that can be contracted through oral sex, and even those each have less than 10% transmission rates orally. Most doctors will not bring up condoms during fellatio or throat swabbing unless you do, but if in evaluating your comfort with risk you decide that you want to incorporate condoms and throat swabs into your blow jobs, that would be a part of your specific safeR sex regimen.

The truth is that there’s no plug and play formula to answer this question. The journey to discover one’s identity is highly individual. Each person you know who has a label to describe themselves likely came to that conclusion in an entirely unique way. What is true for all of us is that historically queerphobic societies assume each of us are heterosexual. Growing up with that being projected onto you certainly makes it more difficult to discover if you are anything besides straight.

Let’s start with what your sexuality is NOT. Your sexuality is not merely who you have had sex with or been attracted to in the past. Many folks who discover their queerness later in life can feel invalidated by their past heterosexual experiences, or even current heterosexual relationships. Sexuality is defined in who you may be attracted to, have sexual or romantic feelings towards, it’s not a checklist of past encounters. Though your personal history may aid you in this self-analysis, don’t let it limit you.

Your sexuality is not necessarily a permanent label, nor is it a required label. Questions like these often stem from feeling like you NEED a term to describe yourself, a box to put yourself in. Yes, language is certainly helpful in terms of finding community, or locating resources and opportunities. If assigning yourself a label feels comforting, great! If it feels restrictive or stressful, you don’t need one. Not to mention that it is completely normal for the way you identify, or the types of people you’re interested in, to change over the course of your life. Identity is fluid, and it’s okay if your understanding of yourself shifts over time.

Your sexuality is not what society tells you it is. As mentioned, we are assumed straight unless proven otherwise, this is a concept called compulsory heterosexuality. “Comp-het” can pose a huge barrier in discovering who you really are, in more overt ways like leading to self doubt and denial, or in more subtle ways. For example, people who are raised as girls are taught in many ways to compare and compete with one another; to pit themselves against other girls in regards to their sexual desirability. If those people later discover that they are queer, it can be hard to differentiate between feelings of jealousy stemming from comp-het, to feelings of sexual attraction.

In understanding what your sexuality is here are some helpful tools:

● Researching the Kinsey scale – A spectrum that suggests most people don’t fit into rigid categories of “straight” or “gay” but fall somewhere in between.

● Journaling – Writing down your thoughts, experiences, and reactions to different people or situations can reveal patterns over time.

● Consuming a Variety of Media – You only know what you know! Exposing yourself to queer media can help you identify what resonates

There’s no right or wrong way to figure out your sexuality, and there’s no deadline. Whether you find a label that feels right, embrace fluidity, or decide you don’t need a label at all, your identity is valid. Exploration, uncertainty, and change are all natural parts of the process. Trust yourself, give yourself time, and know that whatever you discover is enough.

I tend to sum up “sex positivity” with the phrase “don’t yuck someone else’s yum”.

At its core, sex positivity is fundamentally about non-judgement when it comes to people’s sex lives. It gets more layered than that, but non-judgment is a solid starting place. Some people are kinky, some are queer, some are poly, some aren’t into sex at all – the list goes on.

Sex positivity asks us to recognise that people define sex differently, and that none of those definitions are more “correct” than others, despite society’s long-standing obsession with penis-in-vagina being the only thing that counts. Sex positivity opens up space to talk about things often considered “off-limits” like masturbation, orgasm, or sex work.

There are also ways in which sex positivity impacts how we see the world, society and current affairs. A sex positive worldview often comes with the understanding that things like slut shaming and purity culture didn’t come out of nowhere, they’re rooted in dominant religious frameworks, colonial history, and systems that police whose pleasure gets to matter.

It doesn’t mean you’ll never fall victim to stigma, externally or internally enforced, rather that you strive to unlearn it throughout your life. Being sex positive means being queer-affirming, body-affirming, and caring about the ways in which race, disability, and gender can all impact our lives inside and outside of the bedroom. A sex positive lens allows one to think critically and start to parse through all of the BS, including and not limited to toxic masculinity or unrealistic portrayals of sex in the media.

Many people misinterpret sex-positivity as having the requirement that one be sexually active, have a high libido or have sex often. In reality, sex-positivity fully includes people with low sexual desire or little to no sexual experience (though I’d argue things like fantasising or reading smut totally count as experience). Everyone is welcome, as long as they’re respectful towards and supportive of the self-proclaimed sluts among us too.

Sex positivity is the reason we have such a rich and expanding language to talk about sex.

Terms like “vanilla”, “pegging”, or “fetish” allow us to better depict what brings us pleasure, and understand what brings others pleasure. In that way, sex positivity opens the door for clearer, more honest communication between partners. It encourages authenticity, pushes back against shame, and gives us the tools to talk about sex in a way that’s rooted in curiosity and respect rather than fear or stigma. Sex positivity isn’t only about pleasure, it’s about encouraging sexual practices that promote physical and emotional safety and healthy sexuality, such as consent.

In my observation, the various and evolving types of birth control affect different people in very different ways. With hormonal birth control in particular, I find that a lot can be learned through talking to the people in your life about symptoms that they experienced, as opposed to relying purely on lists of “common” side effects.

The truth is that research around hormonal birth control is under-funded, impacted by patriarchy. I remember firsthand being a sex educator a few years ago, when medical literature still insisted that IUD insertion shouldn’t be painful — meanwhile, I knew so many people who described excruciating experiences. It took years before the research caught up and providers began offering things like local anesthesia for insertion. Birth control is a perfect example of why it’s crucial to move past taboos and actually talk to each other, building community and sharing real information.

That being said, let's walk through some of the different types of birth control, starting with the hormonal options most people think of first:

The Birth Control Pill

There are two types of pills: progestin-only (also called minipills) and combination pills (which contain both estrogen and progestin). Combination pills are more common and slightly more effective. Both types thicken cervical mucus so sperm cannot reach an egg, and some progestin-only pills also suppress ovulation.

Combination pills are taken daily (timing is flexible), while progestin-only pills should be taken within the same three-hour window every day to ensure effectiveness. Packs of combination pills tend to have a week's worth of placebo pills in them, to help you keep on schedule with your pills and remember to take them daily. For some people, seeing a withdrawal bleed during that week provides reassurance that they’re not pregnant.

The IUD

IUDs are a long-term, low maintenance option. A doctor or nurse inserts the IUD through your vagina and into your uterus. There are also two types, hormonal and copper. Hormonal IUDs, similar to the pill, release progestin and copper has natural sperm-repelling properties. Depending on the brand, IUDs can last anywhere from 3 to 12 years, and some hormonal IUDs can even be used as emergency contraception if placed soon after unprotected sex.

The Shot

Known as the Depo shot or Depo-Provera, this method delivers progestin via injection and lasts about three months before it’s time to get another shot administered by a doctor. It's important to note that the shot can carry some long-term side effects, like decreased bone density, which is why it’s generally recommended not to stay on it for more than two years without breaks.

The Implant

Also known by the brand name, Nexplanon, the implant is a small, progestin-releasing rod that is placed by a medical professional under the skin of the upper arm. It can last up to five years. The IUD and Implant are both associated with heavy bleeding upon first beginning to use it.

The Ring

This small, flexible ring is inserted vaginally by the user and can be left in for three to six weeks depending on the brand. You squeeze the ring and push it up as far as you can, and as long as you can’t feel it when you’re walking around it should be inserted correctly. You can either keep it in during sex (recommended for effectiveness) or remove it. Annovera, a newer brand, is designed for reuse for up to a year – you simply remove it for one week every three weeks.

The Patch

A sticker containing the same hormones as the combination pill, the patch can be applied to certain parts of the body and emits hormones through the skin. The patch can go on your stomach, arm, butt or back and can be worn for a week at a time.

Birth control isn’t just hormonal, though. For example, condoms are a type of birth control that can both protect from STI transmission and be combined with other, long term methods for extra protection. External condoms (applied to penises) are easier to find and more commonly used, but internal condoms (inserted vaginally) are also an option and can be inserted many hours in advance depending on the brand.

Many AFAB people grow older to discover the fertility awareness method (FAM), and wish that they had been taught about it earlier in life. The fertility awareness method requires tracking your cycle in order to know when you are ovulating and avoiding unprotected sex during that period of time. Reading your own basal body temperature (your temperature upon first waking up) can help you better track your cycle, since your temperature rises after ovulation.

Truthfully, tracking your cycle is difficult to do accurately, which is why I don’t recommend this for younger or busier folks. Communities have grown around FAM, often tied to "natural" lifestyle movements that are skeptical of western medicine.

And finally, there’s spermicide, which is a bit less effective than other methods and can also cause microtearing in the vagina. The sponge, diaphragm, and cervical caps are all insertable birth control methods that work with or use spermicide, as well as physically block sperm from entering, making them better protection than spermicide alone.

The average porno may not display it, but talking to your partner before, after and during sex is not only normal – it’s beneficial.

Communication allows your partner and you to better understand your likes and dislikes, which leads to better sex. Communication is where boundary setting happens, you minimise harmful sexual experiences through communicating.

Communication isn’t always easy, even though some experts make it sound like it should be, as a means of encouraging more people to do it. In my experience, things like social anxiety or how well you know your partner can make it feel awkward or intimidating. I’m not going to sit here and tell you it’s easy – it’s not – but it is important.

That being said, there are tips and tricks I can provide that might make communication a bit less intimidating.

Commit to the When

So you want to talk to your partner about sex. Maybe it’s that you wish they would use a tighter grip while performing hand jobs, or that it kind of hurts when they bite your lip during makeouts.

There are really only three times you can bring these thoughts up: before, during, or after they happen. Deciding which of the three you’re going to opt for, and mentally committing to it, can help you picture the conversation ahead of time and make it feel more doable. Bringing it up before sex might mean pausing foreplay to chat, or bringing it up casually on a date night.

Talking during sex could sound like those “oh, right there!”, “that feels good, keep going”, “wait, a little slower”, or “I want your fingers inside me” moments people tend to blurt out. And after could be part of aftercare, though I’d recommend being thoughtful here, giving feedback when you’re both feeling vulnerable can be tricky. Instead of asking “was that good for you?”, which might open the door to some tough feelings, you could try “is there anything I can do next time to make it even better?”

Show and Tell

Sometimes, especially when it comes to sex, showing someone how you like to be touched or licked is more efficient than trying to put it into words. Sex is so societally taboo that our language around it can feel clunky or limited. Start simple, something like “this is how I touch myself”, or by physically guiding their hand with yours.

Bring an Arsenal of Terminology

You’ll feel more empowered to talk about sex when you actually know what words you have to choose from. Sure, there’s “faster” and “slower”, if any communication is represented in porn it’s usually just that. But people tend to forget about things like angle, type of touch, and pressure. As a huge Megan thee Stallion fan, one of my favorite lines of hers is “stop licking my pussy hard, that shit aggravating”. Upon first hearing it, I found it revolutionary, because it’s so true and I’d never heard anyone put it into words.

Here are some other words to keep in mind:

Pressure: softer, harder, firmer, lighter, deeper

Speed: slower, quicker

Angle: stay flat, more sideways

Type of touch: gentle strokes, circular motions, tapping, squeezing, dragging fingertips

Rhythm: steady pace, build up slower, pulse a little

Intensity: tease me a little, don't stop, stay consistent

Location tweaks: a little higher, a little lower, just to the left/right

Verbal encouragement: yes, just like that, don’t change what you’re doing

Do the Boundary Work

Identifying your own boundaries is a journey, especially if you’ve been raised to be a people-pleaser, or are under the impression that setting boundaries is a downer. It isn’t. Boundary setting allows your partner to know you more authentically, and helps keep you safe.

Discovering your boundaries often requires finding ways to connect with yourself, to communicate with yourself. This could look like journaling, meditating, or masturbating. A good starting place might be: if someone else’s feelings weren’t a factor, what would I say?

Of course, IRL there is some negotiating that can go into making sex pleasurable for both parties, but this can be a good way of identifying what you want in the first place. The act of saying no is often not as earth shattering as our anxieties tell us it is.

Through engaging in boundary setting over time, you'll realise that someone else's reaction is out of your control, but that maintaining your own peace and comfort is of the utmost importance. You may well find you'll be glad you stood up for yourself, even if the other person is not.

Incorporate Yes, No, Maybe Lists

Generally, it can be easier to share without feeling like you’re criticising someone when they share as well. One great tool for this is yes, no, maybe lists, a practice that originated in BDSM/Kink communities. Each partner makes a list of different sexual activities (like using toys, spanking, anal play, etc.) and marks whether it’s a yes, a no, or a maybe for them. It’s a fun, gamified way to have conversations that might otherwise feel awkward or heavy.